By Christopher Giles

The kidnapping of schoolchildren in Katsina State, Nigeria has drawn to a close with the return of hundreds of abducted boys, but questions remain over the continuing threat posed by militants in the region.

The Islamist group Boko Haram has claimed responsibility for this latest attack which took place in the north-west of the country, an area not usually associated with the group, raising fears that their influence is spreading.

There are, however, many disparate groups operating in the region, some of whom have declared allegiance to Boko Haram’s leadership.

Over the past decade, Boko Haram militants have been most active in Nigeria’s north-east, predominantly in Borno and neighbouring states.

It was from a school in Chibok, in Borno state, that hundreds of girls were abducted by Boko Haram in 2014, and many of them remain missing. Another mass kidnapping of schoolchildren also took place in 2018 in Yobe, another north-eastern state.

Instability in the north-west, however, has until now largely been as a result of the activities of less-defined armed groups, often called bandits, that have rustled cattle, traded in arms and ransacked villages.

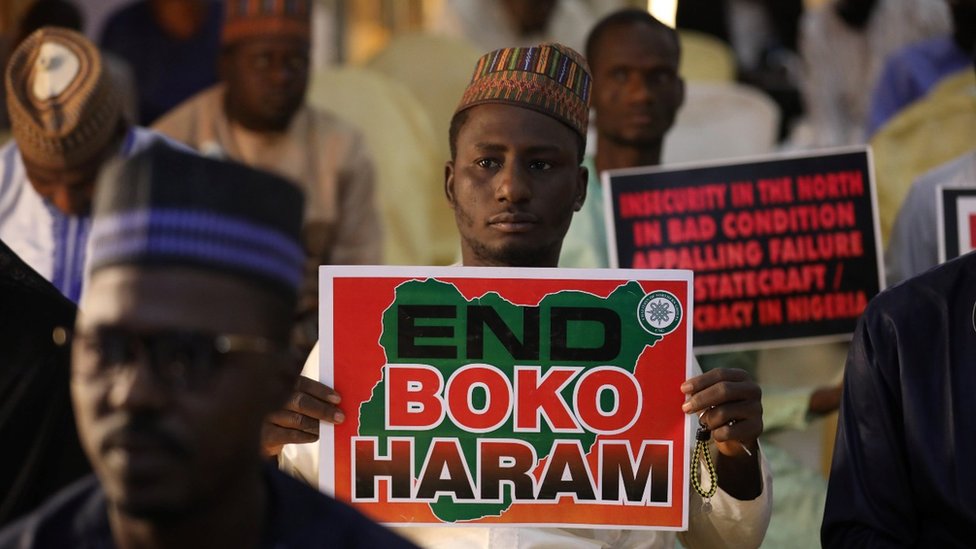

Citizens in northern Nigeria have been urging the authorities to take action against militants

Citizens in northern Nigeria have been urging the authorities to take action against militantsThere are now fears that Boko Haram is expanding its sphere of influence.

“What is unprecedented is the scale of this operation, because it exceeded what bandits have ever done and resembled what only Boko Haram has done,” said Jacob Zenn, editor of the Jamestown Foundation Terrorism Monitor.

“It seemed to be somewhat of a synthesis of bandit area of operations, bandit tactics [but] with the scale of Boko Haram and the ideology of its leader Abubakar Shekau,” said Mr Zenn.

The governor of Katsina insisted bandits were responsible for the recent attack. Although Boko Haram published a video on its outlets showing the boys captive.

According to a report by AFP news agency which quoted security officials, Boko Haram recruited local gangs to kidnap the schoolchildren.

At its peak in about 2012, the group’s influence stretched across the north-east of Nigeria and into the neighbouring countries of Niger and Chad.

Although the group now controls less territory, the attacks have continued despite claims by Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari that the group has been “technically defeated”.

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES

IMAGE COPYRIGHTGETTY IMAGES“The attacks are not uncommon. It is the number of victims that is unprecedented,” said Nkasi Wodu, a peacebuilding and human rights practitioner based in Nigeria. “Both Boko Haram and bandits in the north-west and north-east are running amok almost unhindered.”

This has led to calls for a change in the government’s approach to security.

“How can one explain the movement of the bandits in their hundreds on motorcycles without being detected?” the Sultan of Sokoto, a prominent Nigerian Islamic leader, has said.

“What happens to intelligence-gathering that this heinous plan was not uncovered before it was hatched?” he added, referring to the latest attack in Katsina.

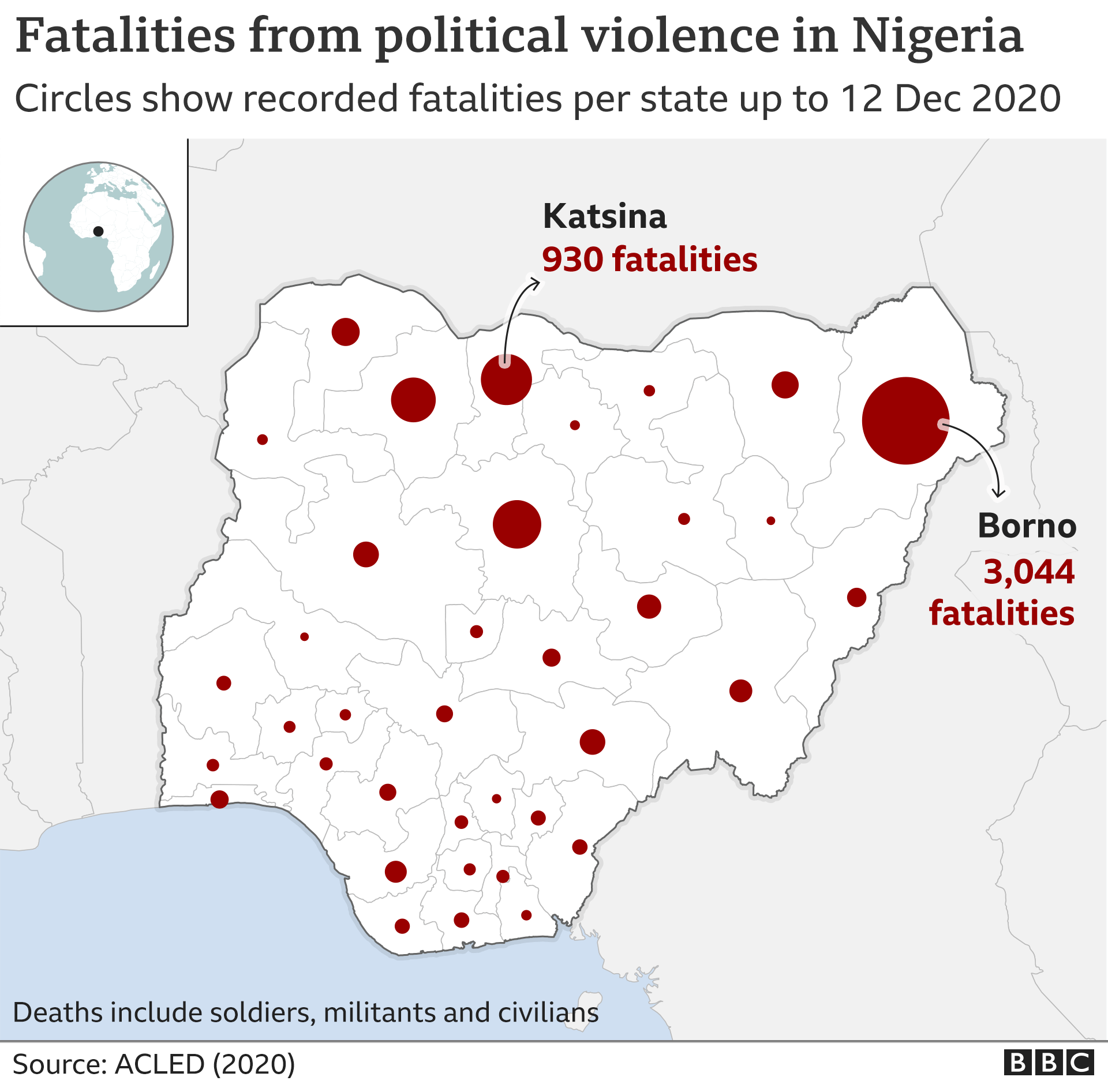

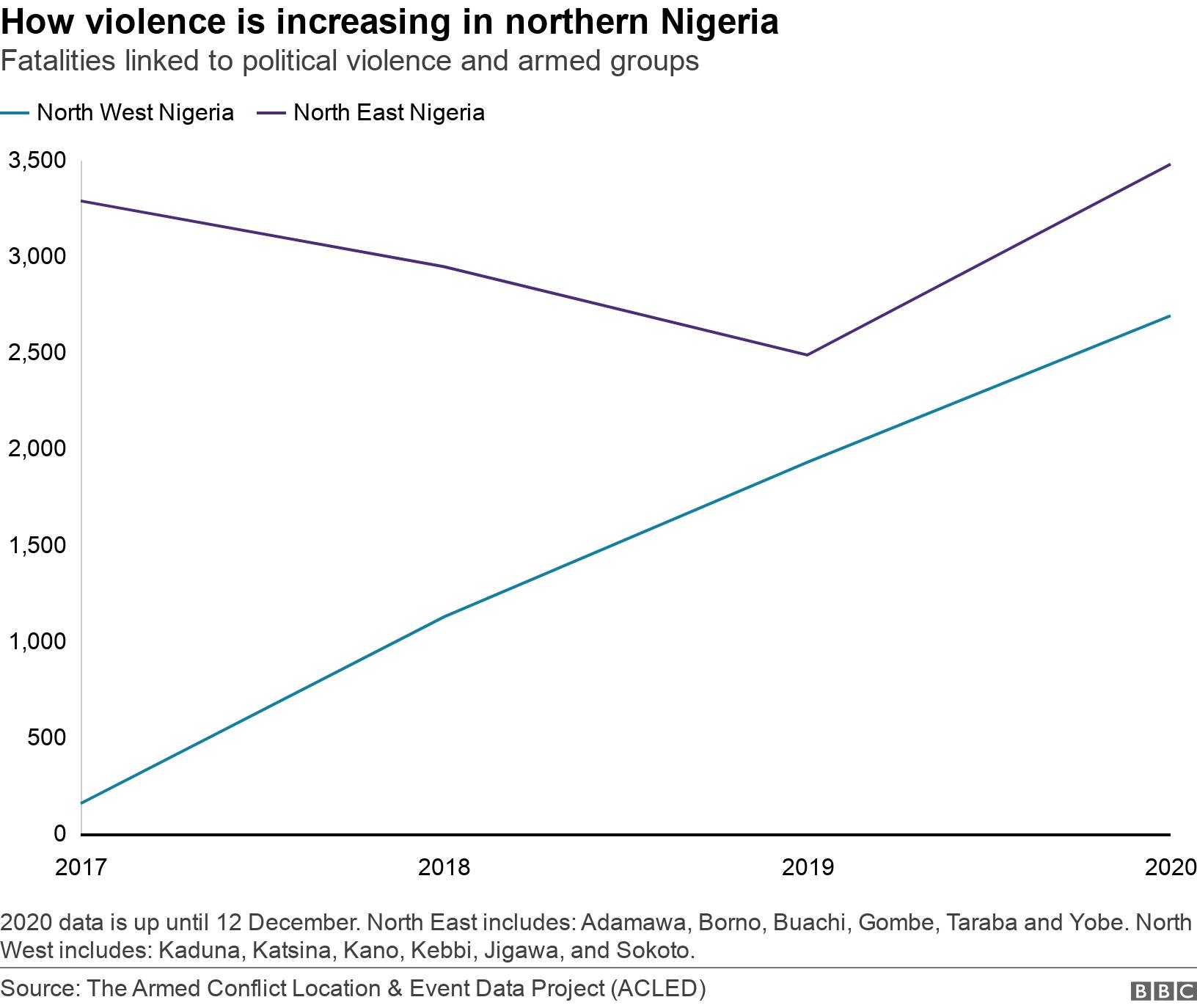

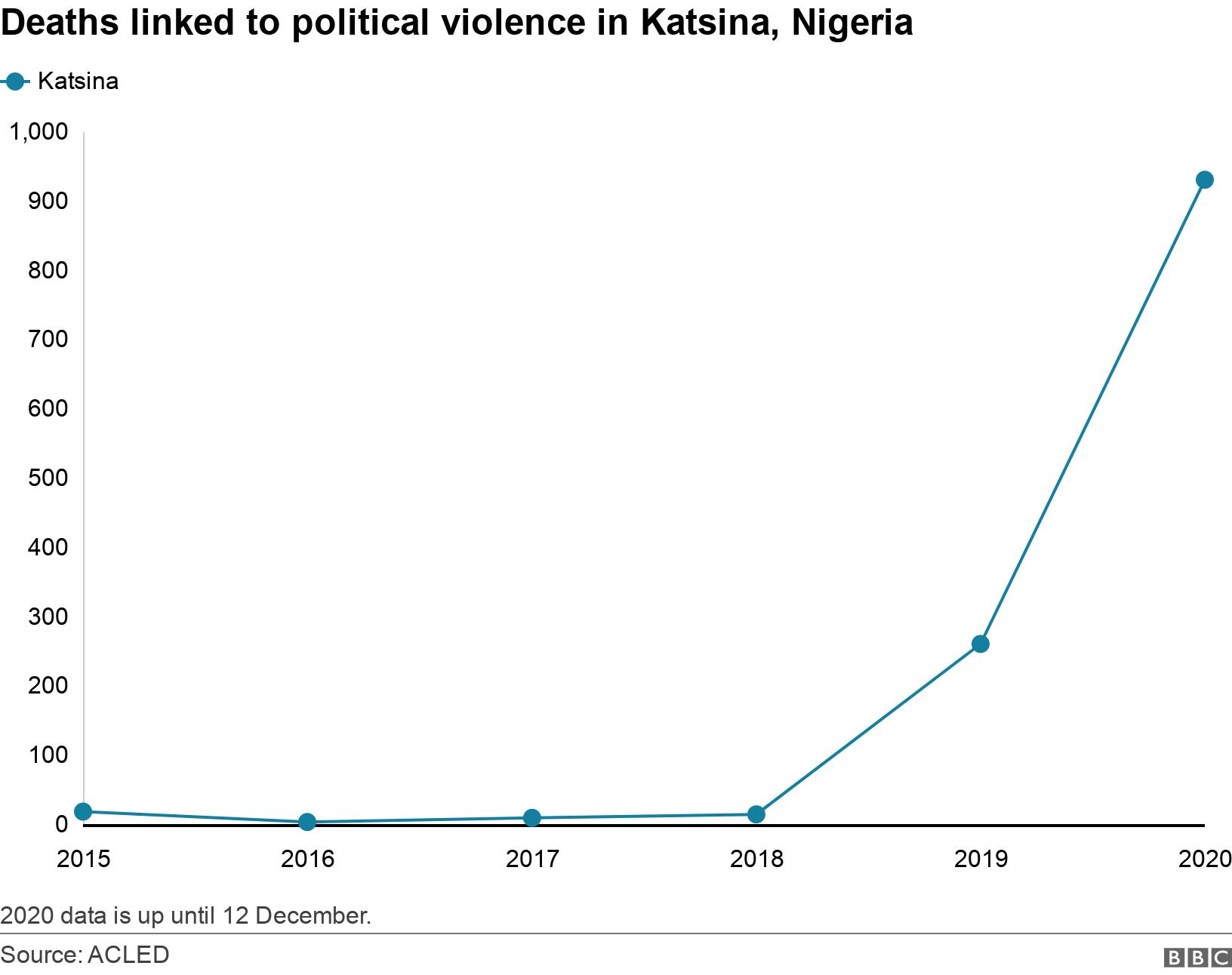

Using data from the Armed Conflict & Event Data Project (ACLED), which collects information from local and international media reports, we’ve looked at the levels of violence across northern Nigeria.

The north-east has long been the epicentre of violence in the north. That’s still the case, and deaths as a result of violence have increased this year.

“The increase in fatalities largely has to do with the successful ambushes on the military – Boko Haram and Iswap [a splinter group affiliated to the Islamic State group], as well as Boko Haram’s own massacres of civilians,” said Mr Zenn.

However, the north-west has also seen a significant increase in violence.

In the past few years, Zamfara, Katsina and Kaduna states in particular have seen rises in the number of deaths related to armed groups and political violence.

The reasons behind the instability in the region are complex.

A report published earlier this year by the International Crisis Group said “violence is rooted in competition over resources between predominantly Fulani herders and mostly Hausa farmers. It has escalated amid a boom in organised crime, including cattle rustling, kidnapping for ransom and village raids”.

It’s also reported that jihadist groups are looking to take advantage of the worsening security situation.

“Over the past year there have been lots of pledges of loyalty to Boko Haram leader Shekau from north-west Nigeria – and Shekau has acknowledged that,” said Mr Zenn.

Boko Haram also has a splinter group that operates in the north-west, known as Ansaru. The al-Qaeda-affiliated group has largely been dormant and has claimed a sparse number of attacks since it was formed in 2012.

What has been the military’s strategy?

The Nigerian military’s approach has mostly focused on air strikes to target remote militant bases.

Official military Twitter accounts regularly post videos and images, claiming to have successfully eliminated bandit groups.

In February this year, Nigerian security forces claimed to have killed more than 250 militants and bandits at a base belonging to Ansaru in Kaduna.

Ground operations tend to be avoided because of the large loss of military lives they often incur.

A major problem, however, has been the widespread public distrust of the security forces.

“In terms of bandit attacks, many communities have complained that when they send reports of impending attacks to the military or police, there is no response. This breeds mistrust against security agencies,” said Mr Wodu.

The government has also pursued a “super camp” strategy in the north-east, setting up large, well-protected strongholds.

Security analysts say that this strategy has made the large cities more secure – but the rural areas vulnerable.