If any African needed an understanding of the spiritual lens with which colonial Europe viewed the continent and its peoples, Richard Henry Stone’s ‘In Africa’s Forest And Jungles: Six Years Among the Yorubas’, an American missionary, who was a representative of the Southern Baptist Convention’s account of his sojourn in Africa during the nineteenth century, tells the story very poignantly.

Among others, Stone had written: “They (Nigerians) are the tortured slaves of superstitions which destroy everything like peace of mind, and they know nothing of that happiness that is found in every place worthy of the name of a Christian home. In this life they are in constant dread of the unseen power of malignant spirits; and in death, not a single ray of hope disperses the gloom of the grave: they seem to pass away in sullen, speechless despair. In religious things, their minds are a desert, a wilderness”.

However, when it came to writing about the Osoogun, Iseyin local government, Oyo state-born Bishop Ajayi Crowther, Stone had said that before he left Africa, he “became well acquainted with him and learned to love and venerate him very sincerely; for he was gentle, humble and sympathetic, and was a great comfort to me in a time of deep distress”.

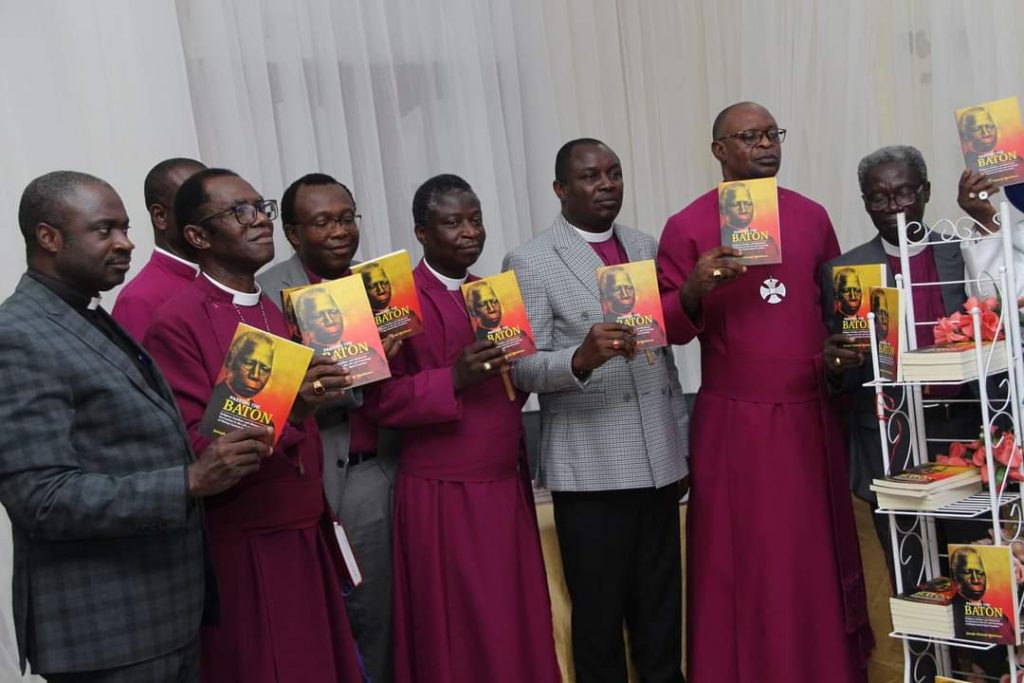

Since then, so many writers have told the story of that 12-year old captured African boy sold to the Portuguese by slave hunters in 1821 and who became so useful to the propagation of the Christian faith in Africa, translating the bible into Yoruba. It is said that a Sierra Leonean former Igbo slave boy named Christopher Taylor, who worked under Crowther as the Bishop of the Niger in the 1800s, translated the bible into the Igbo language. However, the most recent of works on Crowther is the book, ‘Passing The Baton’, authored by the Archbishop of the Anglican Church, Dr Joseph Olatunji Akinfenwa. A rework of his PhD thesis, in the book, Akinfenwa highlighted Crowther’s consequential struggles to weave together a Christian faith in Africa and how his descendants and family tree have continued this work of situating the church in the entire project of spreading the faith.

The major thrust of Akinfenwa’s book is to interrogate the succession of family trees in ministerial assignments in Nigeria. For instance, how many children of Christian ministers are retained in the church of their parents, long after their forebears had translated mortality for immortality. In this book, he cited so many instances to back up his claim. However, as the Yoruba will explain this dilemma in their quip that the faith of the father is helpless to rescue his child from Armageddon – “igbagbo baba o gb’omola”, this has been the case in both Pentecostal and Orthodox churches over the centuries.

Akinfenwa’s methodic elevation of this work from a doctoral thesis, with its turgid academic lingos and cants, into an accessible work of art, is commendable. The book is both a historical work as well as a theological shuttle into the essence of faith and the expectations of the world from a Christian believer. It is one which all must have and read, for enlightenment, teaching and understanding of the role of Christian church fathers in the propagation of the faith, irrespective of religious leanings.