As children in the typical agrarian world of Northern Cross River State, Nigeria, it was the tradition for mothers to leave their young babies in the care of the older ones while the mothers went to distant farms. Across the day the older children grappled with the occasional frustrating cries of their baby-siblings, sometimes grappled with hunger and even with the sheer anxiety of being left alone at home to fend for their younger siblings without an adult. At the onset of evening hours mothers began trickling back from the farms. For the child whose mother had not arrived, it was a great moment of anxiety, of frustration and worry; and it was this situation that gave birth to the usual children’s short song, addressed to the beetle called “Whukpalib” in the Bette-Bendi lingo. The short song goes: “Whukpalib-eh, whukpalib, whukpalib-eh, whukpalib, everyone else is arriving [home], but my mother isn’t arriving!”

This was the song that leaped to my lips early this month as I flipped through the list of names in the 2020 world ranking of universities as released by the Centre for World University Rankings. My non-arriving mother in this case was, first, the name of any Nigerian university, and then the name of any African university. Three of the first four mothers to arrive were neighbours from South Africa: the University of Cape Coast at number 268; the University of KwaZulu-Natal being number 477; while the third neighbour was University of Johannesburg, which is the 706th on the list out of the 2000 universities recorded. The other African university is Cairo University, Egypt, which is the 558th on the list. The next neighbouring mother to arrive was Uganda’s Makere University, which was established in the same 1948 as Nigeria’s premier university, the University of Ibadan, by the British colonial government. Makere came up as the 923th best university in the world; yet, my real mother, the first Nigerian university to arrive, didn’t come up until I got to serial number 1,163, where I found our own great University of Ibadan. This places this best Nigerian university four times below the best in South Africa, University of Cape Coast. Down the list another Nigerian mother arrived at number 1,882, the University of Nigeria. This is only 118 universities away from the bottom of the list of 2000; and that ended the arrival of my Nigerian university mothers from distant farms.

Beyond the anxiety about seeing or not seeing the names of Nigerian universities coming up on the list, there were musings and reflections and some fun, too, around me as I went down the list. I was always pleased to find the names of some of the universities around the world that I’ve had some close career and professional involvements with, or have heard about, or whose histories I am familiar with, or in which I have some friends. For instance, my heart experienced glow when I saw the names of a few of the universities in New York which I’d visited as a Fulbright scholar. Similarly, I was excited to find on the list names from among the cluster of universities in India’s Tamil Nadu axis, whose doctoral candidates I have examined for over 15 years now. The Ghanaian age mate of Nigeria’s University of Ibadan, University of Ghana, Legon, whose campus I am reasonably familiar with, came up also a bit late at number 1,346. Even at this number, it turned up earlier than Kumasi’s Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, which surfaced at number 1,460. The arrival of certain four universities or so stirred up goose pimples all over me. They are Wuhan University (243), Wuhan University of Technology (555), Wuhan University of Science and Technology (1381) and Wuhan Institute of Technology (1494). Whenever a Wuhan name appeared, I thought of my nose mask and hand sanitizer as emblems of covid-19!

Malaysia’s Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (National University of Malaysia) has some special significance to me. I was at this great university in 2005 when the results of the world rankings of universities for that period were announced and Malaysia’s best universities shifted a little backward from where they had been in the preceding rankings. The reactions from Malaysians shocked me pleasantly. The daily newspapers were awash with queries and criticisms and anxiety by almost all Malaysians; and it looked like the citizens were going to ask for the sacking of the minister of education. I bought some of the papers just to show Nigerians what education meant to citizens of some other countries. But not many persons I gave the papers to saw anything striking in the fact that the entire citizenry were so concerned about the state of the nation’s universities. Also, it was at this university that I saw how much serious-minded governments cherish intellection as a necessary synergy between the gown and the town. Here was where I found directors from government ministries participating actively in the international conference and taking down notes most furiously and copiously to factor into the business of running government. And it was here, too, that I experienced the then-former Prime Minister (He is back as Prime Minister at over 90 years, though), Dr Mahathir Ibn Mohammed, presenting a keynote address on the nation’s language policy, and making vital intellectual contributions that define the boundary between the need to promote one’s mother tongue for use in the domestic domains, and the English language for global and international communication. Yet, Dr Mahathir Ibn Mohammed is a medical doctor by training.

As I went down the list, my mind also reflected on the Nigerian university system. Here is a nation whose University of Ibadan was rated among the best ten universities within the Commonwealth at a time Commonwealth nations looked down on the American university system, generally; but today Ibadan can only take a miserable 1,163th position among world universities. Here is a nation whose universities’ products Chukwuemeka Odumegwu Ojukwu boasted proudly of as being responsible for the scientific and technological feats the Biafrans recorded during the unfortunate Civil War. Here is a nation whose children who have managed to find their way out of the country are excelling everywhere they find themselves in the world. Here is a nation whose products as teachers and researchers are making breakthroughs in all manner of human endeavours wherever the environment is education-friendlier. Here is the same nation forming a huge valley among the world’s universities today. And as I went down the list, images of some of our current gladiators in government flitted past my head. I could see the Honourable Minister of Labour seated, his beard of affluence in place, sipping a healthy cup of coffee or tea, a resting newspaper in front with just the labour-related stories asterisked for him as he thinks of what rough tackle to use in “defeating” the nation’s striking university lecturers. I can see the Honourable Minister of Finance, her venom whetted and ready to strike further at the university lecturers’ salaries. I can see her loyal subaltern, the Accountant-General, with his Director in charge of IPPIS, ready with a fresh punch at the lecturers’ lean earnings. And then as I continued down the list, my eyes stumbled on the image of the Honourable Minister of Education struggling against odds to explain the tragedy entailed in killing education. He looks strange and alone among his colleagues in his favourable posturing towards ASUU’s system-saving interventionist measures.

These images invoked severe pain in me as I looked at my great nation almost absent from the comity of world’s universities. Not that all Nigerians do not know the truth about ASUU’s struggles for the survival of public universities, two of which are the ones represented on this year’s rankings of world universities. Many Nigerians know and are truly sad about the situation. For instance, while we, the Nigerian lecturers, were deliberately starved during the covid-19 total lockdown, my great friend, Kayode Komolafe of Thisday newspaper, strengthened me much. He assured me that when the history of this country will be written, ASUU will have a place of gold in the account as that is the only union that is sincerely fighting a lone battle for the survival of Nigeria’s universities. When he mentioned that ASUU is fighting a battle that all Nigerians ought to be fighting, I remembered my Malaysian and Ghanaian experiences. At independence in 1957, Ghanaians decided to insulate education from politics such that any government, military or civilian, that tampers with the nation’s education, faces the wrath of the entire citizenry, not just the actors in the education sector alone. Another great mind, Pastor Udeme Ukpong, used the story of the snake which bit repeatedly the hand that wanted to save it from a fire as an illustration of how Nigerians are destroying or biting incessantly the ASUU that is battling to save the nation’s education system. And who are these snakes? The government, which should take the glory for having a healthy system of education, the parents who should be happy that their children are being given a globally competitive education quality; and the students themselves, who should be appreciative of being properly baked for survival in a competitive world. The student body, the National Association of Nigerian Students (NANS), especially under the successive treacherous and leadership of Yinka Gbadebo (under the administration of President Goodluck Jonathan) and Bamidele Akpan (under the current administration of President Mohammadu Buhari) simply spent more time daring the lecturers to please the government than fighting for the improvement of the education sector.

Further, in a rather pensive, almost mournful tone, one of my most gracious and promising former students, who now resides in Britain, said to me, “Sir, we all know what ASUU is fighting for. The Union certainly wants the system to survive, but I doubt that the Union will achieve its goal because the British economy will be seriously and negatively affected if the Nigerian education system regains its good state of health. You need to know how much this country [Britain] makes every year from fees paid by Nigerian students; and the people here [in Britain], who control our governments back home would never allow any positive changes in the state of our education”. Not that this was new to me or to my colleagues; but the import of the statement is that it was coming from a non-ASUU member, a patriotic, altruistic and well informed Nigerian who told me she was still proud of her Nigerian university education background in spite of the lack of facilities and the strikes that had truncated her learning while here.

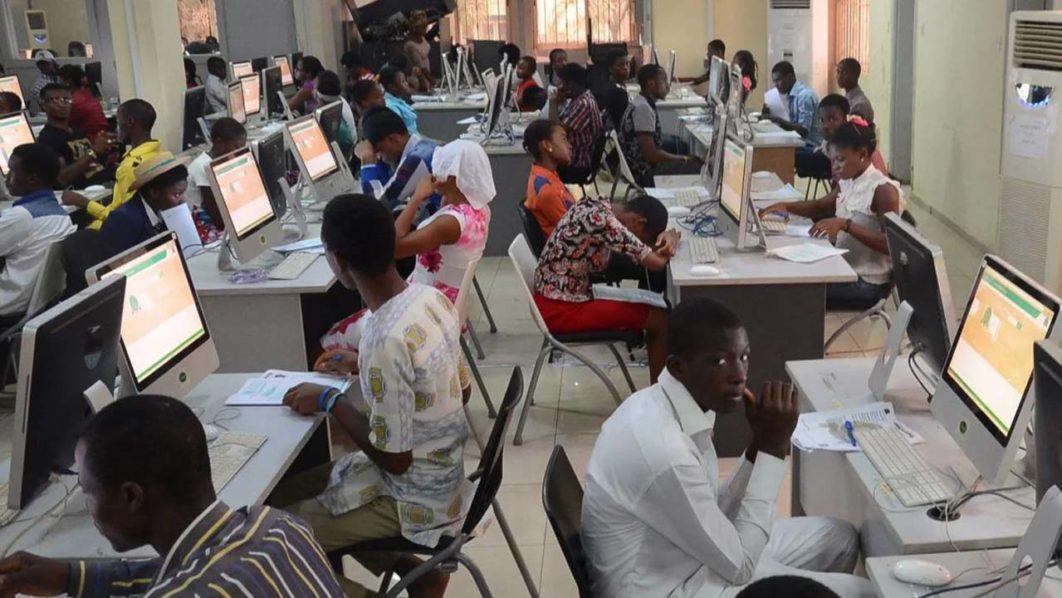

In sum, while the atmosphere in other countries must be charged now with robust discussions about how their countries fared in this year’s world ranking of universities, Nigerians, with only two out of the nation’s over 200 universities making the list at 1163 and 1882 respectively, are quiet and going about their businesses as if this nation is no longer a part of the world – or can only share the world’s woes such as in covid-19. Still worse is the fact that while the rest of the world’s governments are either celebrating the enhanced positions of their universities in the rankings or working towards improvement in the education sector, the gladiators in the Nigerian government led by the ministers of labour and finance, and armed with the crude implement known as IPPIS (Integrated Personnel and Payroll Information System), is busy plucking the few feathers that are left in the body of the bird called Nigerian University System through the current sacking of contract and visiting lecturers. Thus, like the racist former American White police officer, Derek Chauvin, who savagely pinned down the African American George Floyd to death late last month with his knee, the knee of the Nigerian government is on the neck of the Nigerian university system, and the system cannot now breathe given the sacking of lecturers on contract and visiting appointments, government’s dragging of feet over the renegotiation of its agreement with ASUU, government’s reluctance to pay the lecturers their long overdue earned academic allowances, government’s repeated reneging on the provision of fund for revitalization, and the now routine amputation of even their already paltry monthly deceptions called salaries. Strangely, however, the Nigerian students themselves, their parents and most of the Nigerian populace are either urging the government to press its knee harder on the neck of the lecturers or struggling to lend a knee to government’s murderous one already on the neck of the nation’s education system, while the advanced economies that have programmed the system to this death watch with satisfaction, their universities showing up very early in the list of any world rankings of universities. Meanwhile, the Nigerian nation remains represented in this year’s world rankings by only the University of Ibadan, which comes up at 1,163, and the University of Nigeria, which takes the 1,882th position out of the 2000 universities on the list.